When I studied Engineering at university, I learnt about various electro-mechanical systems and the fundamental principles upon which their functions are established. One of the subjects that really enthused me was systems engineering and the complex process of product design and manufacture. I have since worked on many different systems in different industries and most of my work nowadays involves helping designers and managers to improve their design and innovation processes.

One of the principles that I like to promote is the importance of the Gemba. Gemba/Genba (現場) is a Japanese word for the ‘site’ or ‘place of action’. The term became part of management lexicon due to the growth of lean thinking. A designer or engineer can define a system, subsystem or component to an incredible level of detail without going to the Gemba. But going to the Gemba can have a massive impact on their work, due to the different aspects of reality that it helps them to appreciate. If you are familiar with Gemba and its sister principle of Genchi Genbutsu (現地現物‘go and see’) then you’re probably thinking that this is nothing new, and you’re absolutely right. The two questions that I would like to raise and shine a light on are (1) what is the Gemba? And (2) what should you do at the Gemba? To help, I will mention two anecdotes.

It was mentioned in a 2004 article in the Chicago Sun-Times that Yuji Yokoya, a Toyota engineer, was given the responsibility of re-engineering a new generation of the Toyota Sienna minivan for the North American market. It is said that he drove more than 50,000 miles across America to understand the Gemba. This trip is suggested to have inspired him to develop an all-wheel-drive version and improve the crosswind stability, turning radius, the general handling, interior space, cargo flexibility, seat quality, and also add various other functions and features. The following year, Sienna sales went up by 50%. Not a bad Gemba investment.

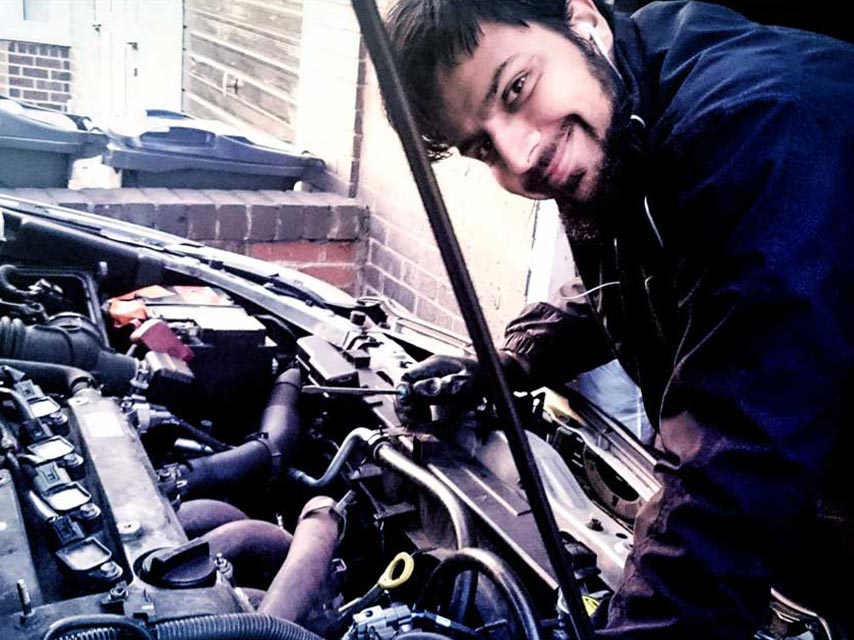

The second anecdote is a bit more personal. Recently, my car started leaking coolant, and after spending a small fortune to change the radiator, thermostat and water pump, I realised the head gasket had blown. For those of you who don’t know, the head gasket is a sheet of metal that sits between the cylinder head (top) and engine block (bottom); it ensures good compression and keeps gases, coolant and oil separate. Unfortunately changing the head gasket is one of the most time-consuming and costly car repairs because it involves taking the engine to pieces, literally. I reluctantly booked my car in for the repair, but I kept thinking of how much I could learn by doing the repair myself.

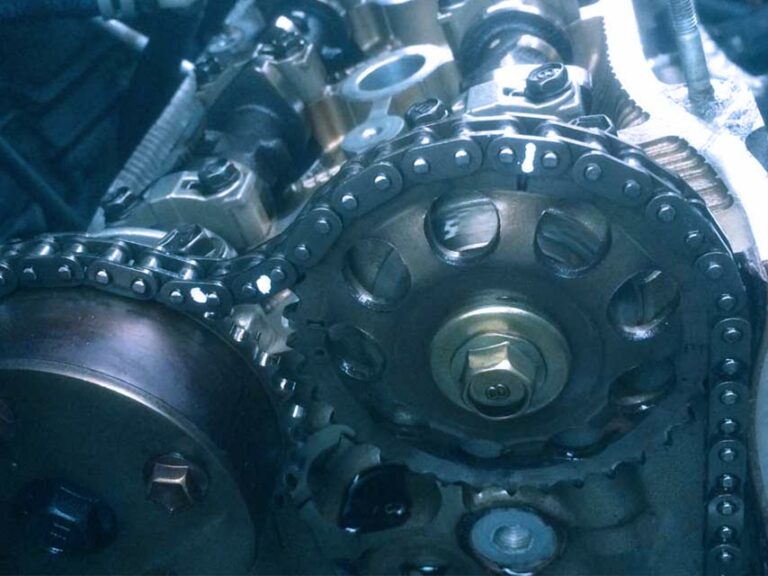

After a few days of deliberation, I decided to go to the Gemba and take on the challenge. I got hold of the car service manual, ordered the necessary parts and tools and got to work. Removing parts, one by one, I took pictures, videos, notes, and contemplated how different aspects of the system worked. I also identified many design issues, and thought of potential improvements. Disassembly was not an easy task; stubborn and difficult to reach nuts and bolts made me wonder whether the designers even considered ‘design for maintenance’. But after days of perseverance, I lifted my treasure from the engine, a dirty, damaged head gasket. The good news is that installing the new gasket and assembly was much easier than disassembly, and the car is now working fine. The great news is that I understand the Gemba principle so much more now and I learnt so much by applying it!

The first question I raised was what is the Gemba? And in my experience, many people understand it to mean an end product, its environment and how it operates. The Sienna anecdote exemplifies this understanding. I don’t disagree with this view, but I think that experiencing and understanding more ‘Gembas’, including a product’s manufacturing process, assembly, maintenance, parts being replaced, parts and products being transported etc. can lead to better designs and in turn better products.

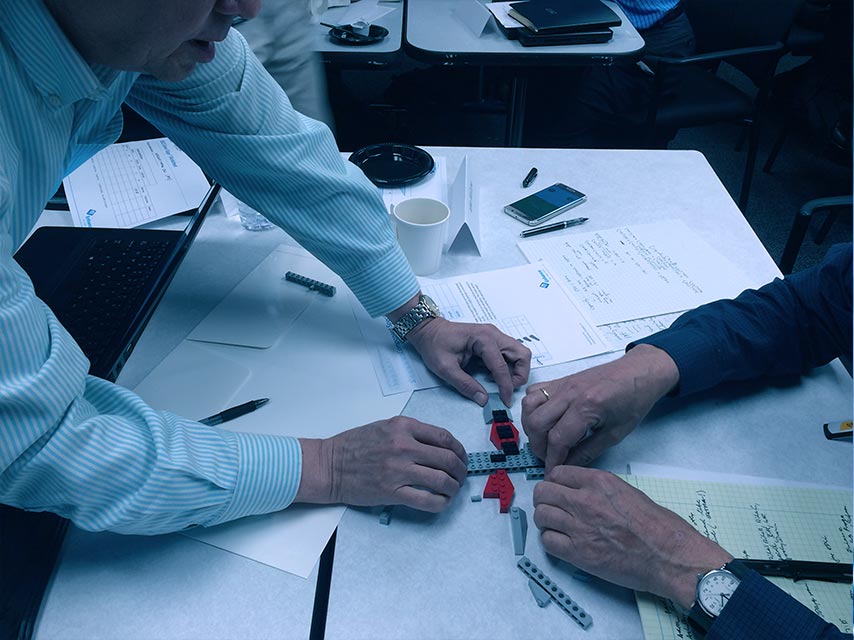

This brings me to the second question: what should you do at the Gemba? I think that you should try to do more than observe. Through my little project, I gained a much deeper understanding than I have ever had by studying, doing design work, or observing car engines. Performing a service operation has put me in a considerably better position as an advocate for ‘design for service’. It might be argued that systems and products vary, and doing a service repair may not make sense on many products, which may be true. But I think if we spend some time to determine activities that would help to understand and appreciate different Gembas, it might help us in NPD to design better products for the future.